| Plate: Markus Hofstätter |

While many choose to focus on the fast-moving world of modern photography, Markus Hofstätter, an award-winning photographer, builds his art on patience, tradition and tangible connection. Using large-format analog cameras and labor-intensive wet plate processes, he creates portraits that are as much about human interaction as they are about photographic technique. I had the opportunity to (virtually) sit down with Hofstätter, learning more about his background, technique and mindset.

His passion for photography began around 2008, well past film’s heyday, while photographing billiards games, a challenge that soon turned into far more than a casual hobby. After learning the ropes, Hofstätter started capturing weddings, local events and more, to make money from his photography. It was all digital, though. But one day, he picked up a Mamiya 645E. While Hofstätter still photographs digitally, from that point on, analog processes became central to his personal work.

|

| Plate: Markus Hofstätter |

With his Mamiya 645E in hand, Hofstätter started taking portraits of people on the streets, which sparked a general love of portrait photography. Another turning point came when he had a friend let him try a 4×5 Linhof Master Technika. The large-format camera sparked a new interest for him.

However, Hofstätter says he got a bit bored with that as well. He then stumbled on a video of photographer Ian Ruhter making massive collodion wet plates and fell in love. “I tried to learn that by myself on 4×5 plates, and I failed so badly for many months. I only made black plates, so that was very frustrating,” he said. But he didn’t give up. He picked up a book by Quinn Jacobson and started making his own chemicals, eventually figuring out the process. Hofstätter says he hasn’t looked back since.

These days, Hofstätter uses a Kodak 2D camera (which he modified, as you can see above) for studio setups and a Century No.2 for outside. He’s mostly working with historical processes like wet plates and salt prints.

He explained that he is a very independent person and loves to work with his hands, which is part of why he’s so drawn to the old analog processes. It is stressful trying to get everything right for a successful print, but Hofstätter says the demanding process keeps him sharp, a kind of creative tension that helps him focus. “I was always a little stressed or anxious before pool tournaments,” he said. “Then I learned that when the stress comes, it means I get extra energy. It means I’m ready now, and I’m going to be extra careful and extra good because the stress is here. It’s the same in the darkroom.”

Hofstätter sees benefits for portraiture from the slow analog process. His sessions result in only a single plate, which is drastically different from a portrait session with digital cameras. Of course, that also introduces challenges. You only have one shot to produce an image, after all. Hofstätter said that means you have to really figure out the individual before starting to take the photograph.

|

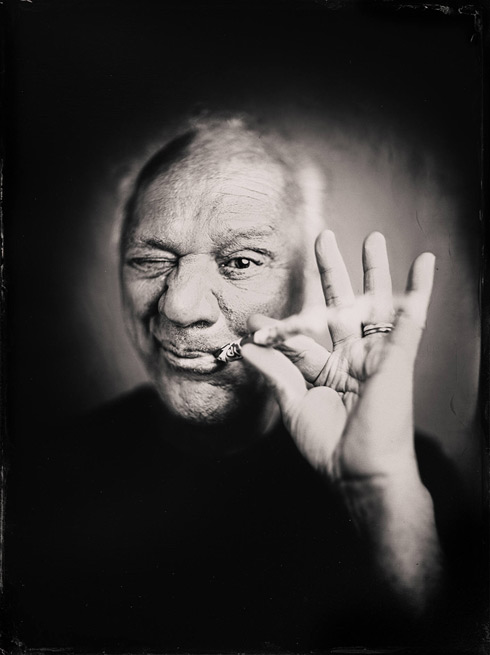

| Plate: Markus Hofstätter |

Hofstätter also explained that with wet plate processes, the subject is involved in the whole process. They get to see the plate getting prepped, the camera set up, the development and so on. That means he gets a lot more interaction with the people he’s photographing, which lends itself to a different type of connection. The longer exposure times also lend themselves to unique results for portraiture. “I get to capture something different with the process because you have to sit still for two to three seconds,” he explained. “You cannot fake good energy if you’re not in a good mood for three seconds. So you get a different kind of personality, a real personality.”

“If you want really great portraits, take at least 30 minutes per person.”

Looking at Hofstätter’s work reveals truly intimate, powerful portraits. Creating portraits like that involves a deep knowledge of how to work with people. “Portrait photography is mostly not about technique, it’s about how you handle people,” he said. It also requires a lot of trust and connection with the subject. When asked how he builds that trust, Hofstätter emphasized the importance of time. His main suggestion: take time. “If you want really great portraits, take at least 30 minutes per person,” he said. “Chat with them before you even get started. Get to know who they are.”

|

| Plate: Markus Hofstätter |

Of course, every person is different. Each individual will require a slightly different technique to get them comfortable in front of the lens. One method he likes to use is to have the subject close their eyes and only open them when they are ready. Then, when the eyes open, he takes the photograph. It gives the subject time to collect their thoughts and relax before he creates the image.

When asked whether he plans to explore other historical processes, Hofstätter said it isn’t a priority right now. “I want to create, I don’t want to try. I figured it out now, and I just want to create portraits. At some point, when I’m limited, then I’ll try something new,” he explained. He gave an example of this problem-solving from when he was photographing a couple comprised of a woman with really dark skin and a really light man. The process is only blue-light sensitive, so she nearly completely disappeared. So, Hofstätter had to figure out a different recipe for his chemicals and tweak his lighting, which enabled him to get all of the skin tones to better handle such situations.

That doesn’t mean Hofstätter is entirely opposed to trying new things, of course. A few years ago, he came across an antique retouching desk dating back to the late 19th and early 20th century. While many only associate retouching with digital processes and Photoshop, retouching has been around nearly as long as photography itself. After staring at it for those few years, he finally decided to put it to use. In a recent video and blog post, Hofstätter shared the process of learning how to retouch a plate with the antique table, which he said is more comfortable than the LED table he had used in the past.

Hofstätter was retouching his plates prior to buying this table using Photoshop. He explained that his retouching is always to make the digital copy look like the original. Seeing a plate in person is a much different experience, since tilting it or moving around it changes how the shadows and highlights appear. Because of that, he’ll dodge and burn in Photoshop to get the digital version closer to the original. These days, he also shares videos of his plates to provide a better view of how they look in real life.

|

| A preview of “The White Rabbit,” an image included in his storytelling-based portrait series. Plate: Markus Hofstätter |

As his practice continues to evolve, Hofstätter is preparing a book that pays tribute to the individuals who have inspired him. At the same time, he is delving into more story-driven work, weaving narratives into his plates while continuing with these historical processes. You can see more of his work on his website, his Instagram or his YouTube channel, and you can sign up for his newsletter to stay up to date on his Inspired series.